ConsentFix: A New way to Phish for Tokens

A look at a new phishing campaign, ConsentFix which utilises click-fix style techniques to steal auth tokens.

Intro

Last week our friends over at Push Security released a blog on a new Phishing technique they had observed in the wild. Named ConsentFix, the technique shares similarities to ClickFix and FileFix, where a user is coerced into a copy/paste behaviour, however this technique looks to steal an OAuth token to be used for authentication. The Push Security blog covered a lot of the technical detail for the technique, along with the related fundamentals for OAuth, so I’m not going to go through those again.

Instead, I’m going to look at replicating the attacker activity in my lab, to see what telemetry is produced, and what detections/hunts can be put in place.

Attack Replication

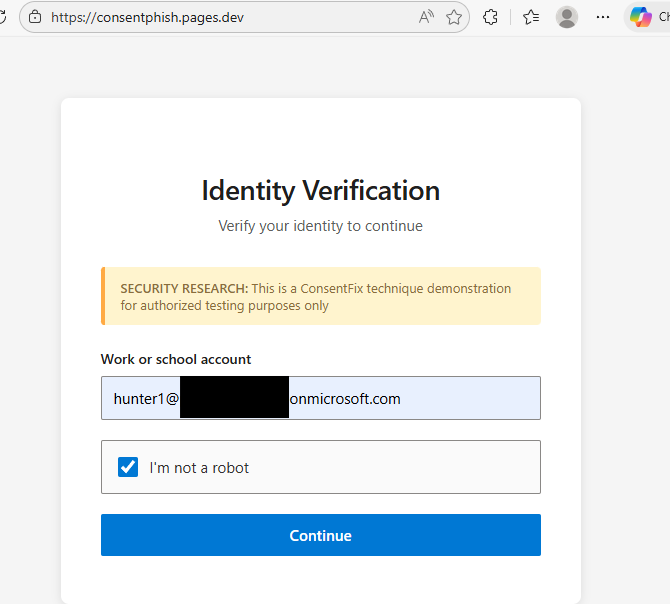

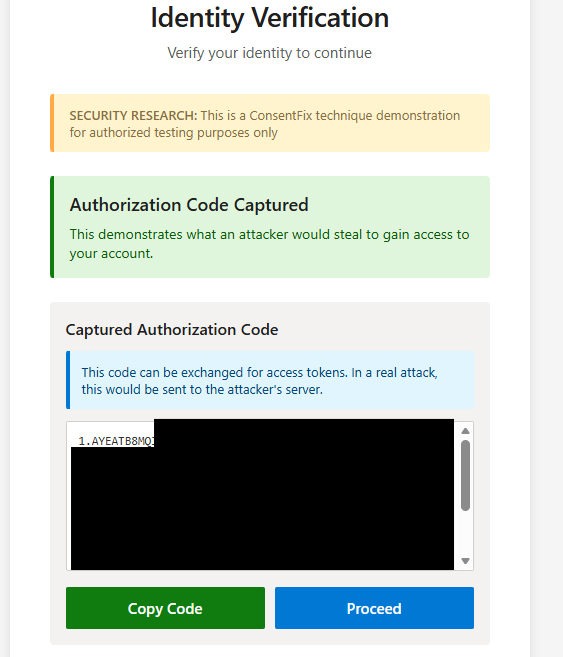

I’ve created a simple phish page to mimic the one observed in the real world attack by Push. This phish page first requires the user to enter a valid email address which needs to match one in a list. This means only victim emails can progress to the next stage. I’m hosting this as a simple HTML page on CloudFlare.

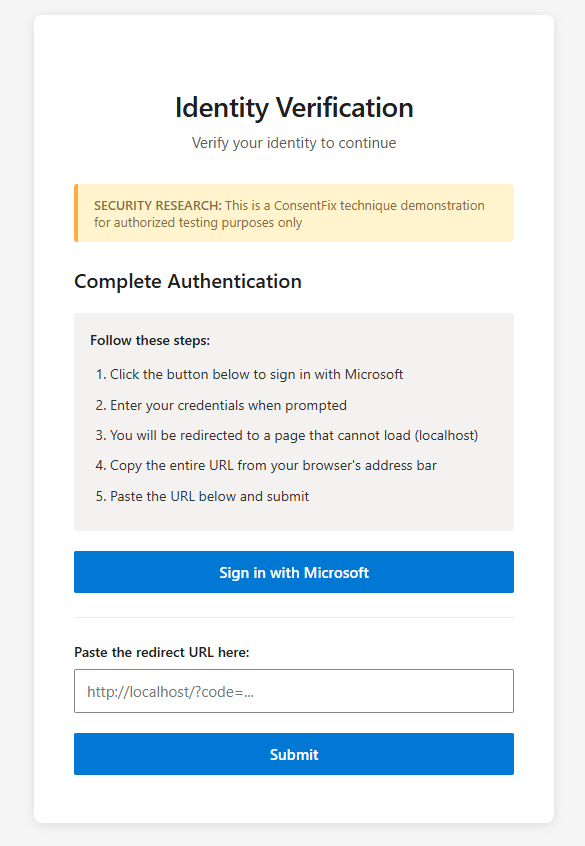

Following that, the user is given instructions to sign in to their Microsoft Account, and to copy the URL in the address bar, and paste it into a text box. They’re told the connection to local host will fail. In real world scenarios, the phish page and instructions would be a lot more convincing!

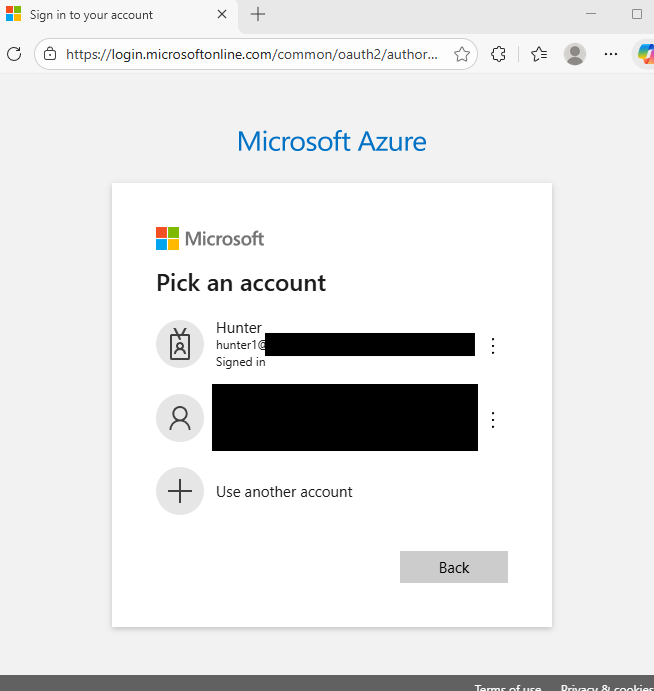

When the “sign in with Microsoft” button is clicked, the user is presented with a legitimate Microsoft Login portal. As already mentioned in the Push blog, if the user is already signed in, they do not need to enter any credentials. This can provide additional trust to the user, as it reduces an action that they need to take.

Let’s take a quick look at the Microsoft URL we’re accessing.

https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/authorize?client_id=04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46&response_type=code&redirect_uri=http://localhost&resource=https://management.azure.com/&state=REDACTED&prompt=select_account The first part of the URL is the typical MS authentication endpoint

The next part, is the client_ID that we’re authenticating to, which in our case is Microsoft Azure CLI:

- client_id=04b07795-8ddb-461a-bbee-02f9e1bf7b46

Next up, the response_type value is telling MS to use OAuth authorization code flow.

- response_type=code

The redirect URI is a key element, this is redirecting to local host, which we touch on more below.

- redirect_uri=http://localhost

Next defined is the resource we’re requesting access to, which is Azure Management, giving us the required API permissions.

- resource=https://management.azure.com/

And the final part, we’re prompting to use the “account picker” option in Windows Sign In, allowing the user to select their logged in account.

- prompt=select_account

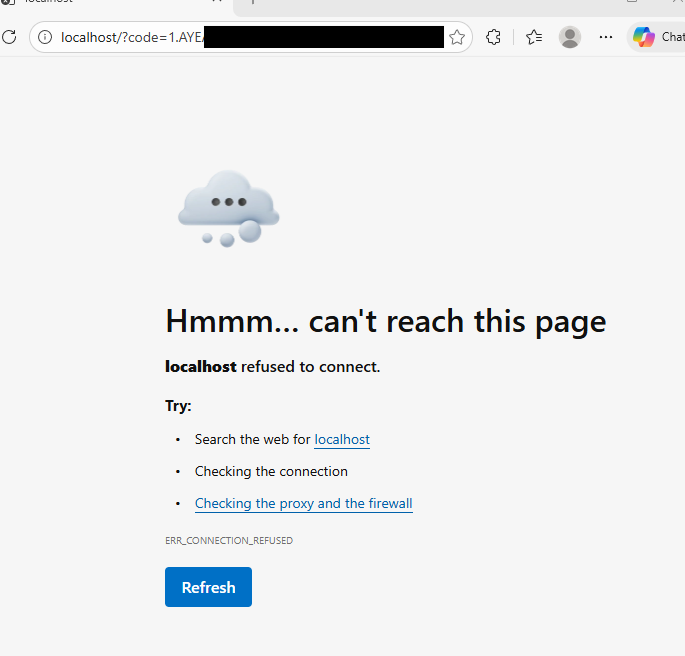

Now back to the attack flow. As we’re redirecting to local host, we’re met with a refused to connect page. However note the contents of the URL in the image below, it contains an authorisation code.

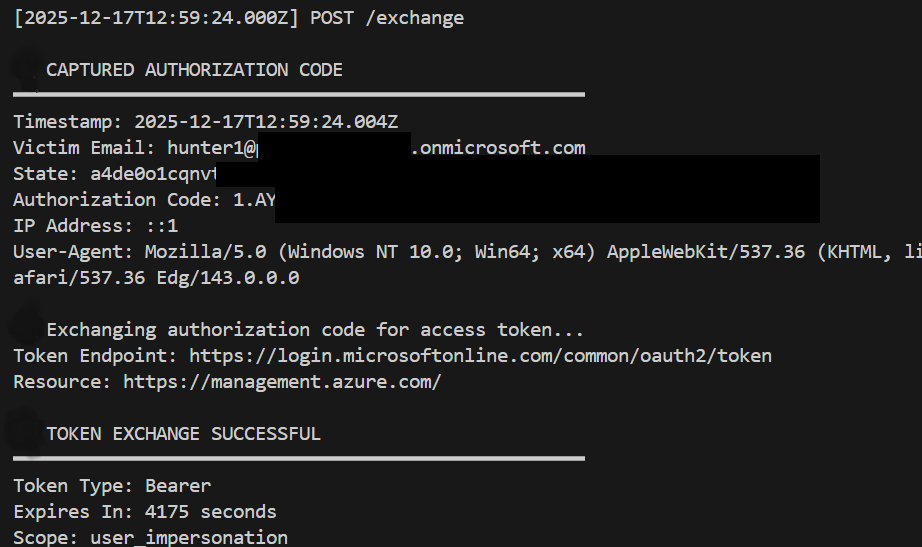

After having the user copy this URL, and paste it into the text box, and then click “Next”, the code is sent to our C2 server.

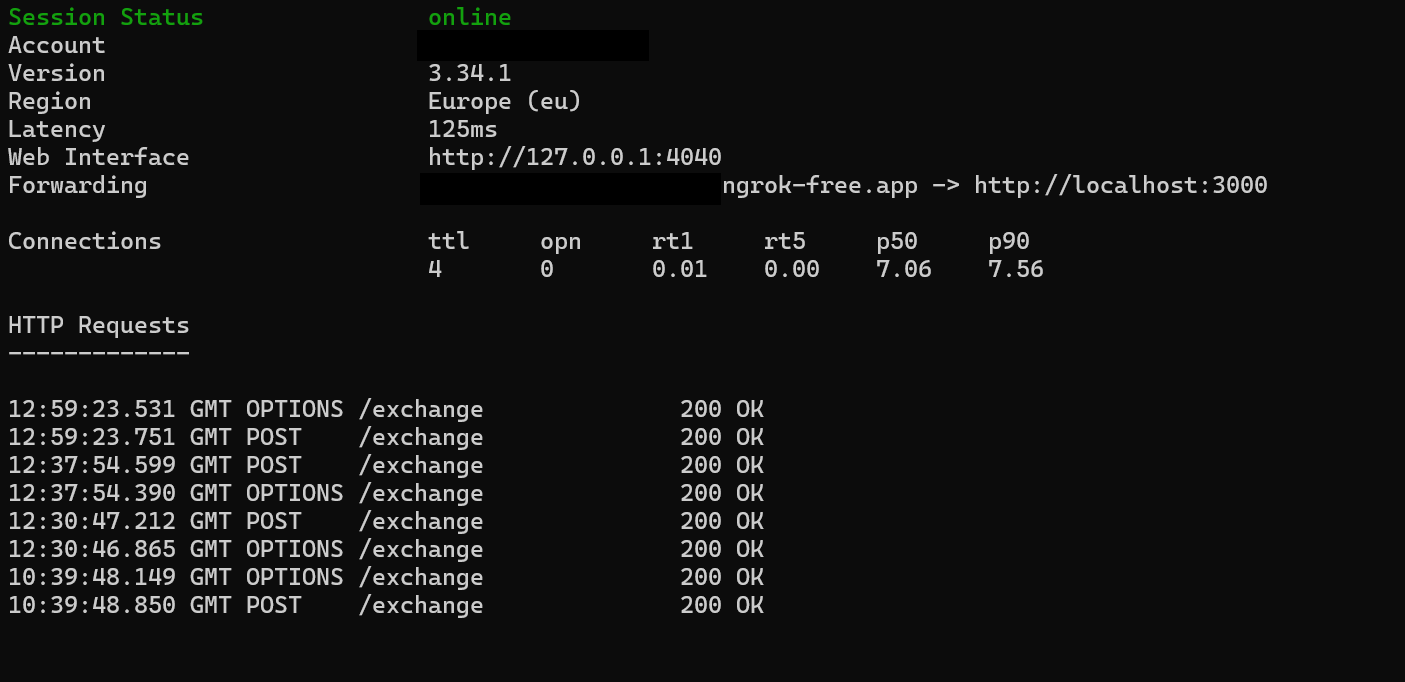

In this case, we’re using NGrok, which is listening on a local port, on our attacker machine. When the user submits the URL, the web page sends a POST request to our NGrok URL/exchange, which is forwarded to our Local Host.

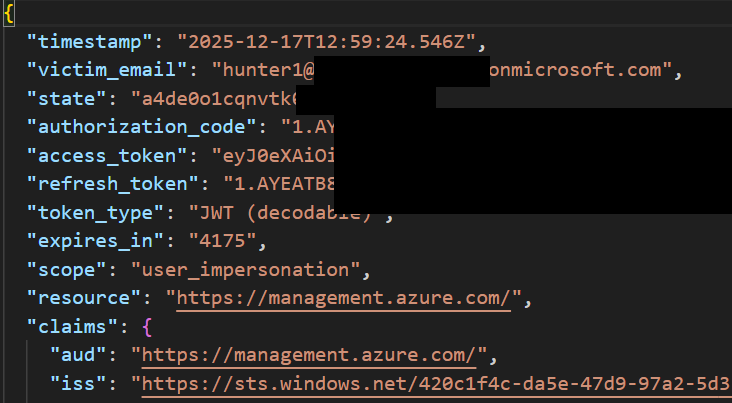

From here we capture the authorisation code, and then exchange it for access tokens.

An Access token and refresh token pair are then written out into a file, which can be used for further activity.

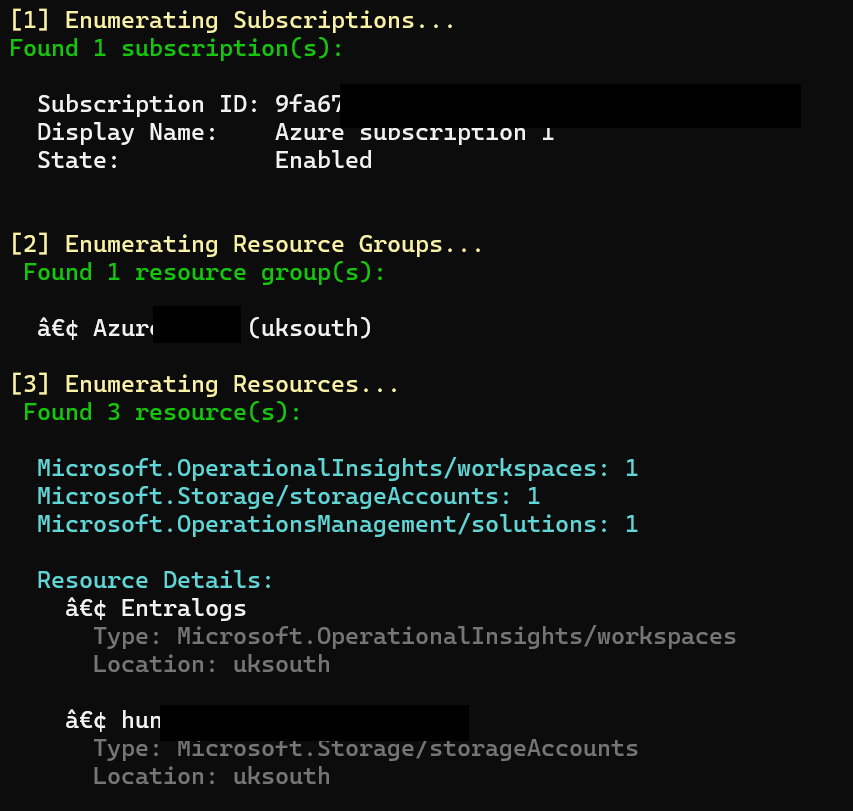

From here, we can use those tokens from our attacker machine, for whatever we like. Here’s an example of some basic enumeration:

And there we have it, access into our Azure environment, from a simple copy and paste phish. Now you may be thinking, “but I have Conditional Access, I’m safe!”. Well, think again!

Conditional Access Flaws

As we found out in my previous blog, there are flaws in conditional access when it comes to access/bearer tokens. We have our same conditional access policy applied from our previous blog, where we require a compliant device. We also had token protection enabled, however that broke the app and meant we couldn’t authenticate to Azure CLI. This is because Azure CLI is not a supported application for token protection, see my previous blog for the full list.

Dive into Telemetry

Our first login is the legitimate one by the user, to the Microsoft Authentication page, prompted by the Phishing Page. We can see the incoming token is a PRT, and is bound to the user’s device which is compliant. This event is present in SigninLogs within Entra, as it’s an interactive logon, and is the user generating the authroisation code for the attacker to steal.

{

"TimeGenerated": "17/12/2025, 13:56:06.000",

"AADIPAddress": "86.142.241.139",

"DeviceCompliance": true,

"AADLocation": "GB",

"AADASN": 2856,

"CIDRASNName": "British Telecommunications PLC",

"DeviceName": "HUNTERWORK",

"signInSessionStatus": "bound",

"IncomingTokenType": "primaryRefreshToken",

"UniqueTokenIdentifier": "IgfBgHoZq0Gck8I1l_ATAA",

"Identity": "Hunter",

"AppDisplayName": "Microsoft Azure CLI",

"ResourceDisplayName": "Azure Resource Manager"

}Now, the second authentication instance is the attacker, using the access tokens generated. The tokens, acquired by acquiring the authorisation code, authorization code > token exchange. You’ll note that the token identifier is different in the two log entries. This is expected, as it’s not token theft that has occurred here, but rather a stolen authorization code being used to generate new tokens for an attacker to use. This event is present in AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs, as it’s not an interactive logon by the user. You’ll note that the device which the authentication session has occurred against is listed as our managed compliant device. This cannot be accurate, and Entra is again doing incorrect device correlation of authentication sessions. Likely related to Session ID, see the previous post for more on this.

{

"TimeGenerated": "17/12/2025, 13:57:22.918",

"AADIPAddress": "159.28.115.7",

"DeviceCompliance": true,

"AADLocation": "DK",

"AADASN": 208172,

"CIDRASNName": "Proton AG",

"DeviceName": "HUNTERWORK",

"signInSessionStatus": "unbound",

"UniqueTokenIdentifier": "jWilBfqbmkGjhIKDz7ojAA",

"Identity": "Hunter",

"AppDisplayName": "Microsoft Azure CLI"

}How do we detect?

This one is a little more difficult to detect, but there are a few potential hunts we can run. As was the case last time, the full hunt logic can be found over in our hunt repo.

Token Protection Switch with Different IP hunt-2025-038

This first hunt looks at authentications in both SigninLogs and AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs, where the initial authentication is bound to a device, and the 2nd is unbound, and comes from a different IP address. This is also restricted to the “Microsoft Azure CLI” application, and should hopefully catch context shifts for authentications to the app.

User Authenticating to Azure CLI for First Time hunt-2025-039

This hunt looks for cases where users authenticate to Azure CLI for the first time, in the last few days, as compared to a 30 day period. This one has the potential to be resource intensive for larger estates.

Potential ConsentFix URL Match in Proxy hunt-2025-040

This hunt is a bit more of a Dynamic IOC hunt. It looks for the legitimate Microsoft URL used in ConsentFix, focusing on the localhost redirect. This shouldn’t be common in most estates. The regex used in this one also accounts for any Microsoft Client ID (AppID) being present in the URL. While we have seen Azure CLI as the main App used, there is potential for others to be abused as well.

Closing Thoughts

This is a pretty cool technique, and easy to implement. I suspect to see more cases of this in the wild in the coming weeks. The hardest step is getting the user to copy and paste the URL! One other detection capability not covered, would be to look for the MS authentication URL in EmailUrlInfo in XDR logs.

Until next time!